The purpose of this blog post is to demonstrate how one can do scenario discovery in python. This blogpost will use the exploratory modeling workbench available on github. I will demonstrate how we can perform both PRIM in an interactive way, as well as briefly show how to use CART, which is also available in the exploratory modeling workbench. There is ample literature on both CART and PRIM and their relative merits for use in scenario discovery. So I won’t be discussing that here in any detail. This blog was first written as an ipython notebook, which can be found here

The workbench is mend as a one stop shop for doing exploratory modeling, scenario discovery, and (multi-objective) robust decision making. To support this, the workbench is split into several packages. The most important packages are expWorkbench that contains the support for setting up and executing computational experiments or (multi-objective) optimization with models; The connectors package, which contains connectors to vensim (system dynamics modeling package), netlogo (agent based modeling environment), and excel; and the analysis package that contains a wide range of techniques for visualization and analysis of the results from series of computational experiments. Here, we will focus on the analysis package. It some future blog post, I plan to demonstrate the use of the workbench for performing computational experimentation and multi-objective (robust) optimization.

The workbench can be found on github and downloaded from there. At present, the workbench is only available for python 2.7. There is a seperate branch where I am working on making a version of the workbench that works under both python 2.7 and 3. The workbench is depended on various scientific python libraries. If you have a standard scientific python distribution, like anaconda, installed, the main dependencies will be met. In addition to the standard scientific python libraries, the workbench is also dependend on deap for genetic algorithms. There are also some optional dependencies. These include seaborn and mpld3 for nicer and interactive visualizations, and jpype for controlling models implemented in Java, like netlogo, from within the workbench.

In order to demonstrate the use of the exploratory modeling workbench for scenario discovery, I am using a published example. I am using the data used in the original article by Ben Bryant and Rob Lempert where they first introduced scenario discovery. Ben Bryant kindly made this data available for my use. The data comes as a csv file. We can import the data easily using pandas. columns 2 up to and including 10 contain the experimental design, while the classification is presented in column 15

import pandas as pd

data = pd.DataFrame.from_csv('./data/bryant et al 2010 data.csv',

index_col=False)

x = data.ix[:, 2:11]

y = data.ix[:, 15]

The exploratory modeling workbench is built on top of numpy rather than pandas. This is partly a path dependecy issue. The earliest version of prim in the workbench is from 2012, when pandas was still under heavy development. Another problem is that the pandas does not contain explicit information on the datatypes of the columns. The implementation of prim in the exploratory workbench is however datatype aware, in contrast to the scenario discovery toolkit in R. That is, it will handle categorical data differently than continuous data. Internally, prim uses a numpy structured array for x, and a numpy array for y. We can easily transform the pandas dataframe to either.

x = x.to_records() y = y.values

the exploratory modeling workbench comes with a seperate analysis package. This analysis package contains prim. So let’s import prim. The workbench also has its own logging functionality. We can turn this on to get some more insight into prim while it is running.

from analysis import prim from expWorkbench import ema_logging ema_logging.log_to_stderr(ema_logging.INFO);

Next, we need to instantiate the prim algorithm. To mimic the original work of Ben Bryant and Rob Lempert, we set the peeling alpha to 0.1. The peeling alpha determines how much data is peeled off in each iteration of the algorithm. The lower the value, the less data is removed in each iteration. The minimium coverage threshold that a box should meet is set to 0.8. Next, we can use the instantiated algorithm and find a first box.

prim_alg = prim.Prim(x, y, threshold=0.8, peel_alpha=0.1) box1 = prim_alg.find_box()

Let’s investigate this first box is some detail. A first thing to look at is the trade off between coverage and density. The box has a convenience function for this called show_tradeoff. To support working in the ipython notebook, this method returns a matplotlib figure with some additional information than can be used by mpld3.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt box1.show_tradeoff() plt.show()

The notebook contains an mpld3 version of the same figure with interactive pop ups. Let’s look at point 21, just as in the original paper. For this, we can use the inspect method. By default this will display two tables, but we can also make a nice graph instead that contains the same information.

box1.inspect(21) box1.inspect(21, style='graph') plt.show()

This first displays two tables, followed by a figure

coverage 0.752809

density 0.770115

mass 0.098639

mean 0.770115

res dim 4.000000

Name: 21, dtype: float64

box 21

min max qp values

Demand elasticity -0.422000 -0.202000 1.184930e-16

Biomass backstop price 150.049995 199.600006 3.515113e-11

Total biomass 450.000000 755.799988 4.716969e-06

Cellulosic cost 72.650002 133.699997 1.574133e-01

If one where to do a detailed comparison with the results reported in the original article, one would see small numerical differences. These differences arise out of subtle differences in implementation. The most important difference is that the exploratory modeling workbench uses a custom objective function inside prim which is different from the one used in the scenario discovery toolkit. Other differences have to do with details about the hill climbing optimization that is used in prim, and in particular how ties are handled in selecting the next step. The differences between the two implementations are only numerical, and don’t affect the overarching conclusions drawn from the analysis.

Let’s select this 21 box, and get a more detailed view of what the box looks like. Following Bryant et al., we can use scatter plots for this.

box1.select(21) fig = box1.show_pairs_scatter() fig.set_size_inches((12,12)) plt.show()

We have now found a first box that explains close to 80% of the cases of interest. Let’s see if we can find a second box that explains the remainder of the cases.

box2 = prim_alg.find_box()

The logging will inform us in this case that no additional box can be found. The best coverage we can achieve is 0.35, which is well below the specified 0.8 threshold. Let’s look at the final overal results from interactively fitting PRIM to the data. For this, we can use to convenience functions that transform the stats and boxes to pandas data frames.

print prim_alg.stats_to_dataframe() print prim_alg.boxes_to_dataframe()

coverage density mass res_dim

box 1 0.752809 0.770115 0.098639 4

box 2 0.247191 0.027673 0.901361 0

box 1 box 2

min max min max

Demand elasticity -0.422000 -0.202000 -0.8 -0.202000

Biomass backstop price 150.049995 199.600006 90.0 199.600006

Total biomass 450.000000 755.799988 450.0 997.799988

Cellulosic cost 72.650002 133.699997 67.0 133.699997

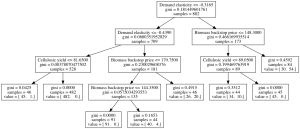

For comparison, we can also use CART for doing scenario discovery. This is readily supported by the exploratory modelling workbench.

from analysis import cart cart_alg = cart.CART(x,y, 0.05) cart_alg.build_tree()

Now that we have trained CART on the data, we can investigate its results. Just like PRIM, we can use stats_to_dataframe and boxes_to_dataframe to get an overview.

print cart_alg.stats_to_dataframe() print cart_alg.boxes_to_dataframe()

coverage density mass res dim

box 1 0.011236 0.021739 0.052154 2

box 2 0.000000 0.000000 0.546485 2

box 3 0.000000 0.000000 0.103175 2

box 4 0.044944 0.090909 0.049887 2

box 5 0.224719 0.434783 0.052154 2

box 6 0.112360 0.227273 0.049887 3

box 7 0.000000 0.000000 0.051020 3

box 8 0.606742 0.642857 0.095238 2

box 1 box 2 box 3 \

min max min max min

Cellulosic yield 80.0 81.649994 81.649994 99.900002 80.000

Demand elasticity -0.8 -0.439000 -0.800000 -0.439000 -0.439

Biomass backstop price 90.0 199.600006 90.000000 199.600006 90.000

box 4 box 5 \

max min max min

Cellulosic yield 99.900002 80.000000 99.900002 80.000

Demand elasticity -0.316500 -0.439000 -0.316500 -0.439

Biomass backstop price 144.350006 144.350006 170.750000 170.750

box 6 box 7 \

max min max min

Cellulosic yield 99.900002 80.0000 89.050003 89.050003

Demand elasticity -0.316500 -0.3165 -0.202000 -0.316500

Biomass backstop price 199.600006 90.0000 148.300003 90.000000

box 8

max min max

Cellulosic yield 99.900002 80.000000 99.900002

Demand elasticity -0.202000 -0.316500 -0.202000

Biomass backstop price 148.300003 148.300003 199.600006

Alternatively, we might want to look at the classification tree directly. For this, we can use the show_tree method. This returns an image that we can either save, or display.

If we look at the results of CART and PRIM, we can see that in this case PRIM produces a better description of the data. The best box found by CART has a coverage and density of a little above 0.6. In contrast, PRIM produces a box with coverage and density above 0.75.

Jan, thanks for the detailed instructions on your post! I ran into a couple of issues when following your instructions to run PRIM on my dataset. Here are the issues and how I fixed them:

1 – I cloned the git repository but my python code wouldn’t import prim. To fix that, added the EMAworkbench to the python sys path by adding the following to the top of the code:

1: import sys

2: sys.path.append(“./EMAworkbench/src/”)

3: (rest of the code)

2 – After that, I ran PRIM and got the following error:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File “Jan_PRIM.py”, line 20, in

box1.show_tradeoff()

File “./EMAworkbench/src/analysis/prim.py”, line 517, in show_tradeoff

if mpld3:

NameError: global name ‘mpld3’ is not defined

This was solved by installing mpld3 with “pip install mpld3”

I hope this helps!

Hi Bernardo. Thanks for the addition on how to get the workbench up and running.

Pingback: Water Programming Blog Guide (Part I) – Water Programming: A Collaborative Research Blog

Pingback: Open exploration with the Exploratory Modelling Workbench – Water Programming: A Collaborative Research Blog

Pingback: 12 Years of WaterProgramming: A Retrospective on >500 Blog Posts – Water Programming: A Collaborative Research Blog